How could consistent use of dual coding support children with religious vocabulary/concepts so they can recall information and make connections more effective?

This was my action research project written earlier in the year as part of the InspiREd Leaders project with the Diocese of St Alban’s. I thought I’d share it in advance of releasing the materials that have been produced from it.

The Conundrum

It is Thursday afternoon; it has been wet play. The midday supervisor wished you good luck as you walked into Year 3. You’ve managed to sort out the argument about who owned a hair bobble between Caitlin and Fajar, and John has finally stopped pointing out the rather damp squirrel on the playground. Afternoon registration is done and it’s time for RE. The children love RE. You’ve managed to get them enthused with the stories, artefacts, engaging tasks and exploration. Today you’re starting a new topic – Christianity: Incarnation! You stick on a well-designed slide and ask “What do you already know” hoping to hear loads of previous learning from Year 2, 1 and even reception. Nothing. You know they did it. You’ve spoken to the previous teachers. They were great at it. They’ve got books full of the stuff. But nothing not a thing. James seems to think it has something to do with a squirrel. It’s going to be a very long afternoon. But where did it all go wrong?

When I first arrived at my current school, this was something that was already being explored but that I was excited to get involved with. Having looked at Rosenshine’s principles (Sherrington, 2019), introduced a new schema and trained staff in retrieval practice (Jones, 2019), we saw lessons becoming increasingly dynamic. However, whilst teachers and pupils had a great attitude toward the subject, there were still considerable gaps in vocabulary (especially subject-specific vocabulary), recall and understanding of key theological beliefs.

Paivio (1979) suggested that the left and right hemispheres of the human brain operate together to process visual and textual information. Paivio presented a model of the coding of visual and textual information called the dual coding hypothesis. According to this theory, if the same information is properly offered to you in two different ways, it enables you to access more working memory capacity. Having been offered visual and verbal stimuli there are two channels that can be triggered by either stimuli. Verbal information is processed sequentially whilst visual information is synchronously processed and together this knowledge is encoded from working memory to long-term memory. Having these two channels (or two memory traces) greatly aids later retrieval from long-term memory back into working memory. (Caviglioni, 2019) Professor Paul Kirschner, calls this “double-barrelled learning” because of the resultant double opportunity of memories being retrieved by either verbal or visual means.

To demonstrate the basics of dual-coding in action, figure 1 shows an activity shared by Caviglioli (2019) which I used as part of the training for our staff.

Figure 2 shows an alternative graphic for the same task. Provided with the same verbal stimuli and questions as Figure 1, this time the process is far more straightforward and less mental effort is involved. This is called the Visual Argument (Larkin and Simon, 1987) where text and images shown together are proven to be simpler to ‘compute’.

Put simply, “People learn better from graphics and words than from words alone.” (Mayer in Caviglioli 2019). In addition, Clark and Lyons (2004) identified six significant benefits to students’ learning when they heavily researched dual coding: direct attention; trigger prior knowledge; manage cognitive load; build schema; transfer to working memory; motivate

I wanted these benefits for the children in our school and so continued to research not only the theory but the design process: as Clark and Lyons (2004) said, “Even the best-planned graphic, if executed poorly or laid out haphazardly, will fail to realise the potential of that graphic to enhance learning.”

The Practical

In developing our icons and diagrams I used what I’d researched to identify three key areas that all graphics must meet: they should be selective, supporting and simple.

Selective: the information to be dual-coded needs to be identified, chunked and organised. (Caviglioli 2019, Sherrington 2019)

Supporting: our graphic creations shouldn’t get used in isolation and become something else that needs to be learnt, adding to the cognitive load. Indeed, the ambition is to provide fewer elements of novel information at once because the dual coding builds instant links to mastered elements of long-term memory (Lovell/Sweller 2021) or as Skemp (2006) would phrase it we are building relational understanding rather than instructional understanding.

Simple: Icons must work in a single colour, have consistency in style and be scalable (able to be understood whether small and not pixelate when made large for display). Accompanying texts and documents created using the graphics should see restraint in the colours used and be of a single typeface. Above all legibility is key; “a clear, bold style with no flourishes or elaborations, is essential ”. (Stevens-Fulbrook 2020, Caviglioli 2019, Simpson 1995)

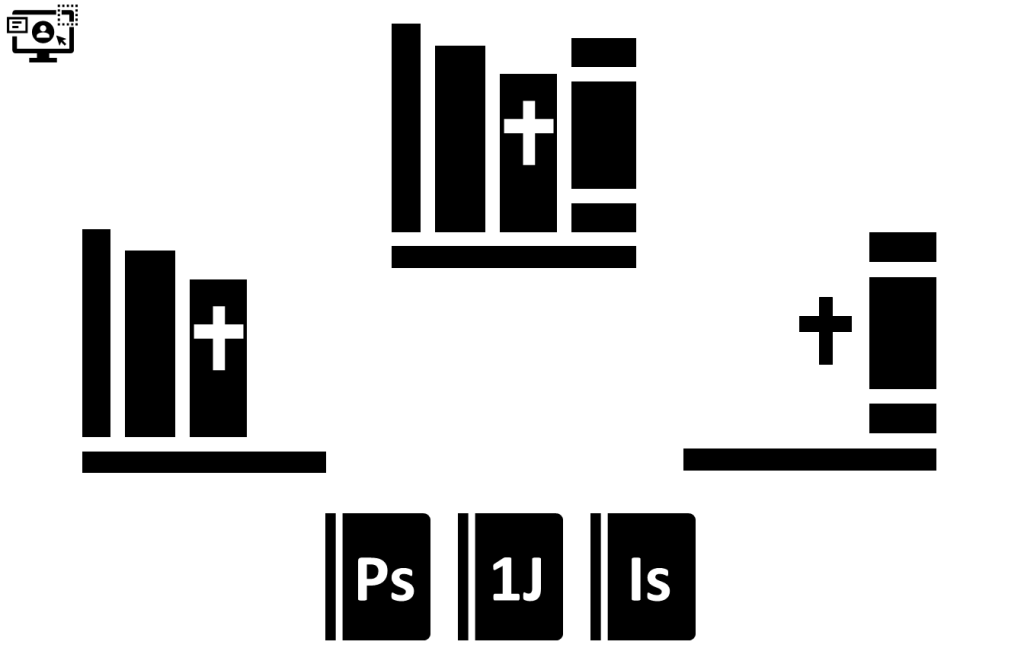

An example of this in action is creating the images to accompany the Bible and Biblical scripture. The image to the left shows the icon we created for the Bible. The hope is to encourage children to understand the concept of the Bible itself, thus the etymology – biblia/biblos (the books/scrolls) – a collection of books rather than a single book.

The cross shows that this is the holy book for Christians. This image has been adapted to show the Old and New Testaments as parts of the Bible. Biblical references can then be framed within this where each book has been given a two-letter shortcode.

The core of Paivio’s dual coding theory is based on matching a visual with a word for the retrieval of simple content. That’s useful as far as it goes. But when the challenge is understanding more complex material, teachers need to use diagrams. By converting abstract concepts or intricate processes into visual structures, key ideas are explained in a way that psychologists say is more computationally efficient. That’s to say concepts become easier for students to understand by being visual, explicit and concrete. (Sherrington and Caviglioli 2021).

In Disciplinary Literacy and Explicit Vocabulary Teaching (Mortimore 2019) supports the idea that dual coding supports more than purely vocabulary and how it can be used in storytelling. Figure 6 shows 3 examples of this from the Year 2 unit on Jesus’ teaching.

Having developed the icons and story graphics they were presented in a simple knowledge organiser format with our assessment strategies built-in. Having shared this with our SLT, this was then put into a trial stage.

Teachers were provided with some training including the pedagogy and ideas behind using the imagery. There was lots of initial interest from teachers (especially as the resources had been provided and they were not required to create their own) and having immediately linked the graphics to assessment meant that teachers felt comfortable and could see the “end game”.

The Wild

Whilst I have received a multitude of feedback on the project so far, for the sake of brevity I will share a case study and the note that teachers in the school have truly embraced dual coding in RE: I have observed displays, videos of children using the diagrams to tell stories, games with icons and a huge deal of creativity. In fully engaging with the topic teachers have been full of praise for the trial and active contributors with their feedback.

Case Study – Year 2: Children in Year 2 are studying incarnation for Autumn 2. They are building on previous knowledge from the year before and the first lesson is used to introduce vocabulary (dual coded) and explore what knowledge has been retained. The Teacher, Miss A, has printed copies of the Vocabulary Sheets to go in their RE books to support children during the unit. The start of other lessons in the sequence are used as an opportunity for retrieval based around using these (as well as looking back to the Autumn 1 unit). Miss A has enlarged the story graphics and they are displayed on the working wall at the back as well as being used when sharing the Bible story from the scriptures.

At the end of term assessment Year 2 children are presented with the hexagons. They have been sliced up and provided to children who work in groups thinking what links them. All children are engaged. Talking to the children it is clear that all are able to understand the graphics and text and access the activity. One group of children are disagreeing about the placement and are creating linear sequences and explaining them to one another. One group has Miss A speaking to them. She is asking questions such as “Could these go together?” “What’s similar/different about Advent/Christmas?” “If you had a blank hexagon what would you put on it? Why?” The responses clearly show if these children are achieving greater depth as she is hoping. In another group one of the children is talking to a visitor about how Christmas is an important time for Christians because that is when Jesus came. “It’s like God’s special gift.” Another child adds, “But Jesus is also God.” “Yeah, that’s why you have the God the Father, Son and Holy Spirit sign but only Jesus is shown. It helps you remember”. The remaining child in the groups offers “incarnation – that’s what it is, it’s Jesus in the flesh.”

I ask one child about the book with ‘Mt’ in it and they clearly articulate that it means this nativity narrative (they know there is another) is from the Book of Matthew in the Bible. They also tell me that its just one of the Books in the Bible because there are lots.

After the lesson I speak to Miss A, she says, “The dual coding has been especially effective in supporting the children to remember stories such as the creation story and the Christmas story as they clearly see the pictures which prompt their memory. It also builds on their understanding because they have to explain the pictures and can’t just label them – it requires them to think deeper and offers scope for deeper justifications. As do they when displayed on our RE boards. The hexagons have also been a useful assessment tool, not only to see how much the children DO know, but also what we need to recap or go further into next half term. It’s interesting to see how they link different hexagons to others and listening to their explanations for this is insightful.”

Our SIAMS inspection took place during the dual coding trial, towards the end of our second unit of RE teaching. The inspector was able to see this in action during her visit saying, “Innovative practice such as the use of pictorial prompts and other ways of making helpful connections are being developed. These are beginning to have a positive impact on pupils’ religious literacy. The carefully planned RE curriculum is well taught at [the school] and pupils are gaining a deep understanding of Christianity and a range of worldviews. They discuss core theological concepts with confidence and enthusiasm. Pupils make good progress as a result of the rich and engaging curriculum which is carefully tailored to pupils of all abilities, including those with special educational needs”. (SIAMS 2021)

The Future

In the immediate future, there are still icons/graphics to create for the remaining term of the year. The subsequent step is to formalise and finalise a wider scope review of the impact. At the moment there is a lot of anecdotal evidence of the positive impact of dual coding in our school. In the time frame used we have not yet been able to ascertain the long-term impact which is key. I also believe that continuing to train staff in using and applying the dual coding elements of our curriculum and exploring the way it can be used for retrieval is key.

I am pleased with the progress seen so far and, insofar as the scope of the research question, believe that dual coding is supporting children in recalling information and making effective connections with religious vocabulary/concepts.

References

Caviglioli , O. 2019 Dual Coding With Teachers

Clark, R.C; Lyons, C. 2004 Graphics for Learning Proven Guidelines for Planning, Designing, and Evaluating Visuals in Training Materials

Jones, K. 2019 Retrieval Practice: Research & Resources for every classroom

Larkin, J.H; Simon, H.A., 1987 Why a diagram is (sometimes) worth ten thousand words. Cognitive science, 11(1), pp.65-100.

Lovell, O. 2020 Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory in Action

Mortimore, K. 2020 Disciplinary Literature and explicit vocabulary teaching

Paivio, A 1979 Imagery and Verbal processes

Sherrington, T; Caviglioli, O. 2020 Teaching WalkThrus: Five-step guides to instructional coaching

Sherrington, T; Caviglioli, O. 2021 Teaching WalkThrus 2: Five-step guides to instructional coaching

Sherrington, T. 2019 Rosenshine’s Principles in Action

Simpson, T. J. 1995 Message Into Medium: An Extension of the Dual Coding Hypothesis.

Skemp, R. R. 2006 Relational Understanding and Instrumental Understanding. Mathematics Teaching in the Middle School, 12(2), 88–95. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41182357

Statutory Inspection of Anglican and Methodist Schools (SIAMS) Report The National Society (Church of England and Church in Wales) for the Promotion of Education.

Stevens-Fulbrook, P. 2020 Evidence Based Practice in Education: Teaching Strategies for the Reflective Teacher (Learning Theories)

Vekiri, I., 2002 What is the value of graphical displays in learning? Educational psychology review, 14(3), pp.261-312.

[…] week, I shared my action research project. Today, I want to share the resources that were created during the […]